In a mid-May video conference with the Peterson Institute for International Economics, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell succinctly vetoed an idea that had been weighing on the minds of treasury bond traders for years.

“The committee’s view on negative rates has not changed. This is not something we’re looking at,” he told the audience.

Even though the U.S. economy is struggling through a severe recession during an extended period of abnormally low-interest rates, the Fed refuses to take its benchmark interest rate into negative territory, fearing that below-zero rates could upend the money market.

While this position might sound reassuring, it actually has sobering implications for the markets long-term treasury bonds, which has seen four decades of almost continuous growth because of falling yields.

The 40 Year Bull Market in Long-Term Treasury Bonds

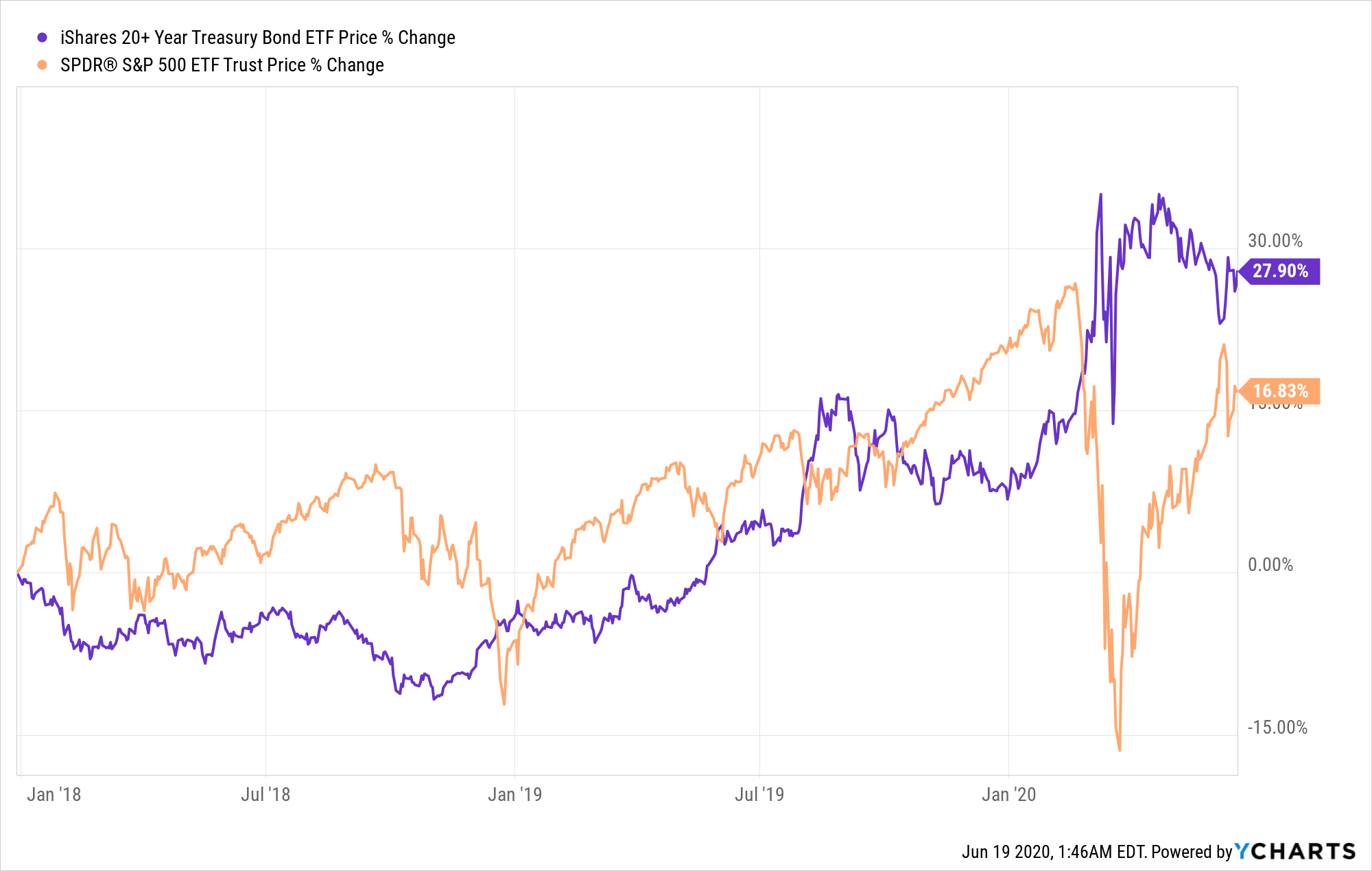

Long-term treasury bonds have been a fantastic investment for most of the last half-century — largely because their prices are negatively correlated with U.S. stocks.

In fact, since the beginning of 2018, the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (NYSE: TLT) has outperformed the S&P 500.

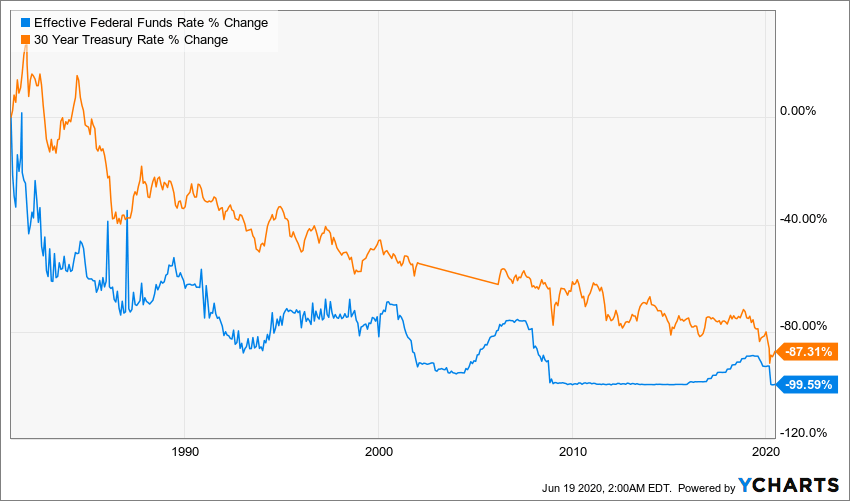

Due to the nature of bond markets, the 40-year-long bull market in long-term treasuries has also brought a 40-year-long decline in the interest rates on these bonds.

The 30-year Treasury yield hit a high of 15% in 1981, but today it’s consistently below 2%. How did it drop so low?

The simple answer is that the bond market made it so. A bond’s yield is simply a conceptual ratio equal to its annual dollar payout — which is fixed — divided by its market price. As traders bid up the price of a bond, its yield falls since its payout doesn’t change.

And for the last 40 years, traders have bid up the price of long-term treasury bonds on a near-consistent basis, leading to steadily falling yields.

But there’s a bit more to this market behavior than meets the eye.

As you can see in the graph below, the market yield of 30-year Treasuries has strongly correlated with the Federal Reserve’s benchmark interest rate, which has also fallen from historic highs in the early ’80s to historic lows today.

That’s because the rate on long-term treasury bonds and the benchmark interest rate — also called the federal funds rate — both fundamentally measure the same thing: the lowest possible cost of borrowing money in America.

Sure, they represent different kinds of loans and different maturities; the Fed’s rate is for interbank overnight lending while the 30-year treasury bond rate measures the cost of long-term government debt. The former is calculated by technocrats in a boardroom while the latter is calculated spontaneously by the whims of the bond market.

But ultimately, the two rates both represent the lowest possible cost of capital in the economy. The bond traders who determine long-term treasury bond rates tend to look to the central bank technocrats who determine the federal funds rate for guidance.

And with that in mind, Chairman Powell’s “this is not something we’re looking at” remark is not nearly as calming as it might sound…

The Best Free Investment You’ll Ever Make

Join Wealth Daily today for FREE. We’ll keep you on top of all the hottest investment ideas before they hit Wall Street. Become a member today, and get our latest free report: “How to Make Your Fortune in Stocks”

It contains full details on why dividends are an amazing tool for growing your wealth.

Why “No Negative Rates” Isn’t As Reassuring As It Sounds

Given that the bond market tends to follow the Fed in setting yields, Powell is effectively putting a ceiling on the price of treasury bonds.

After all, the federal funds rate is the interest rate for overnight loans. If the Fed won’t allow it to dip below zero, then it’s effectively also disallowing longer-term debt from trading at negative yields — lest it freaks out global financial markets by permanently inverting the yield curve.

(Markets generally expect interest rates on longer-term debt to be higher than those on shorter-term debt and they see a deviation from this pattern to be a sign of an upcoming recession.)

If the Fed maintains a zero lower bound in its interest rate policy, it will effectively be telling the bond market that treasury bonds have no more room to rise.

So, what should you buy instead?

Where To Go After Treasury Bonds

Investors have several options to replace treasury bonds as their prices approach the ceiling imposed by the Fed’s zero lower bound in interest rates.

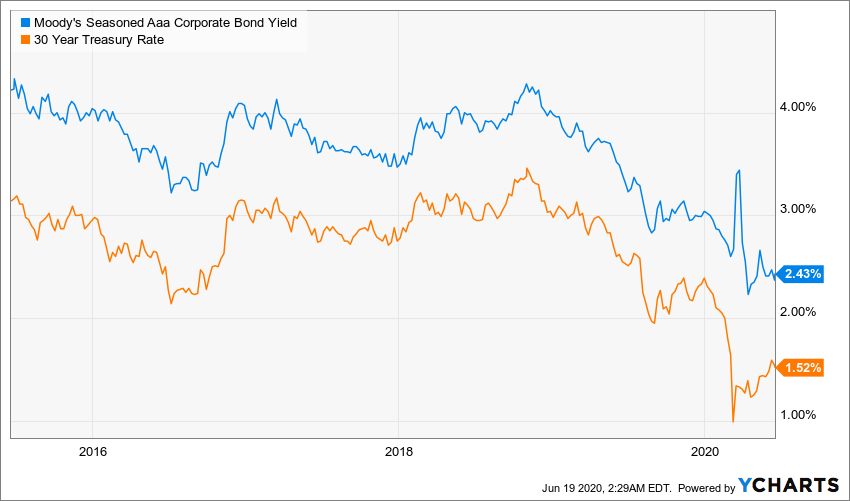

Investment-grade corporate bond yields still have some room to fall before reaching near-zero territory. This implies that corporates could replace treasury bonds for fixed-income investors who still want capital gains from their bonds.

Other commentators have suggested that treasury bond investors should shift some of their holdings into gold, noting that the yellow metal is another asset in which price is not positively correlated with the stock market.

But income investors who are looking for guidance during these strange times are best off consulting experts, like Briton Ryle and Jason Williams of The Wealth Advisory.

Their investment recommendations have provided a steady stream of dividends to their subscribers, even during the recent recession. Click here, to learn more.

Until next time, Samuel Taube Samuel Taube brings years of experience researching ETFs, cryptocurrencies, muni bonds, value stocks, and more to Wealth Daily. He has been writing for investment newsletters since 2013 and has penned articles accurately predicting financial market reactions to Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and more. Samuel holds a degree in economics from the University of Maryland, and his investment approach focuses on finding undervalued assets at every point in the business cycle and then reaping big returns when they recover. To learn more about Samuel, click here.![]()